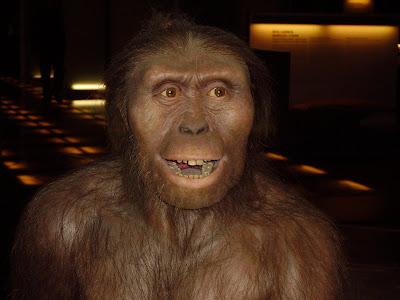

The hominid reproduction of Australopithecus afarensis above and below to the the type of hominid that left footprints that were discovered by Mary Leaky and were dated at "3.75 million-year-old"

and were "tracks preserved in volcanic ash in northern Tanzania. Those prints belonged to A. afarensis, and provided clear evidence of bipedalism."

Mary Leaky's discovery demonstrated that: "Though the short-legged, long-trunked A. Afarensis was able to walk upright, its feet were still apelike," as demonstrated in the picture to the left, "possessing a telltale splayed-out big toe. Because the early fossil record contains no foot bones, scientists didn't know when modern feet — a defining human characteristic necessary for long-distance running — evolved."

The skeletal remains of the most famous reconstruction of A. Afarensis, is almost 40% complete and is shown below was discovered in 1974 in Ethiopia by Donald Johanson. The discovery of this hominin was significant as the skeleton shows evidence of small skull capacity akin to that of apes and of bipedal upright walk akin to that of humans, providing further evidence that bipedalism preceded increase in brain size in human evolution.

"And as the facial reconstruction of Lucy, the most famous of A. afarensis, clearly shows an ape-like facial features and lived between 3.9 and 2.9 million years ago. A. afarensis was of a slight build and was an early ancestor of the genus Homo which includes modern man; the species of Homo sapiens."

"One of the most striking characteristics possessed by Lucy was a valgus knee, which indicated that she normally moved by walking upright. Her femoral head was small and her femoral neck was short, both primitive characteristics. Her greater trochanter, however, was clearly derived, being short and human like rather than taller than the femoral head. The length ratio of her humerus to femur was 84.6% compared to 71.8% for modern humans and 97.8% for common chimpanzees, indicating that either the arms of A. afarensis were beginning to shorten, the legs were beginning to lengthen, or that both were occurring simultaneously. Lucy also possessed a lumbar curve, another indicator of habitual bipedalism."

"Johanson was able to recover Lucy's left innominate bone and sacrum. Though the sacrum was remarkably well preserved, the innominate was distorted like a carnivorous child or infant, leading to two different reconstructions. The first reconstruction had little iliac flare and virtually no anterior wrap, creating an ilium that greatly resembled that of an ape. However, this reconstruction proved to be faulty, as the superior pubic rami would not have been able to connect if the right ilium was identical to the left. A later reconstruction by Tim White showed a broad iliac flare and a definite anterior wrap, indicating that Lucy had an unusually broad inner acetabular distance and unusually long superior pubic rami. Her pubic arch was over 90 degrees, similar to modern human females. Her acetabulum, however, was small and primitive."

A. afarensis demonstrates that "there are a number of traits in the A. afarensis skeleton which strongly reflect bipedalism. In overall anatomy, the pelvis is far more human-like than ape-like. The iliac blades are short and wide, the sacrum is wide and positioned directly behind the hip joint, and there is clear evidence of a strong attachment for the knee extensors. While the pelvis is not wholly human-like (being markedly wide with flared with laterally orientated iliac blades), these features point to a structure that can be considered radically remodeled to accommodate a significant degree of bipedalism in the animals' locomotor repertoire. Importantly, the femur also angles in toward the knee from the hip. This trait would have allowed the foot to have fallen closer to the midline of the body, and is a strong indication of habitual bipedal locomotion. Along with humans, present day orangutans and spider monkeys possess this same feature. The feet also feature adducted big toes, making it difficult if not impossible to grasp branches with the hindlimbs. The loss of a grasping hindlimb also increases the risk of an infant being dropped or falling, as primates typically hold onto their mothers while the mother goes about her daily business. Without the second set of grasping limbs, the infant cannot maintain as strong a grip, and likely had to be held with help from the mother. The problem of holding the infant would be multiplied if the mother also had to climb trees. The ankle joint of A. afarensis is also markedly human-like."

"Climate changes around 11 to 12 million years ago affected forests in East and Central Africa, establishing periods where openings prevented travel through the tree canopy, and during these times ancestral hominids could have adapted the upright walking behavior for ground travel, while the ancestors of gorillas and chimpanzees became more specialized in climbing vertical tree trunks or lianas with a bent hip and bent knee posture, ultimately leading them to use the related knuckle-walking posture for ground travel. This would lead to A. afarensis usage of upright bipedalism for ground travel, while still having arms well adapted for climbing smaller trees. However, chimpanzees and gorillas are the closest living relatives to humans, and share anatomical features including a fused wrist bone which may also suggest knuckle-walking by human ancestors."

Now with the discovery of the 1.5 million year old footprints, researchers how have clear evidence that humankind's first ancestors to walk ot of Africa did so in a manner impossible to differentiate from the types of tracks left by modern mankind.

As the trail of tracks on the right clearly show; the footprints most likely originated from the upright gait of "Homo erectus. Maker of the first stone tools, H. erectus was also the first hominid to leave Africa, migrating to Asia about two million years ago."

Using modern instruments scientists: "By scanning the footprints ( on the right photo) with lasers and measuring sediment compression, then comparing the results to A. afarensis and Homo sapiens, researchers determined that H. erectus had a modern foot and stride: a mid-foot arch, straight big toe and heel-to-toe weight transfer."In a commentary accompanying the study, primatologists Robin Huw Crompton and Todd Pataky say the footprints are "broadly indistinguishable from those of modern humans" and "herald an exciting time for the evolution of human gait."

"Early humans had feet like ours and left lasting impressions in the form of 1.5 million-year-old footprints, some of which were made by feet that could wear a size 9 men's shoe. "The findings at a Northern Kenya site represent the oldest evidence of modern-human foot anatomy. They also help tell an ancestral story of humans who had fully transitioned from tree-dwellers to land walkers.

"The findings at a Northern Kenya site represent the oldest evidence of modern-human foot anatomy. They also help tell an ancestral story of humans who had fully transitioned from tree-dwellers to land walkers."In a sense, it's like putting flesh on the bones," said John Harris, an anthropologist with the Koobi Fora Field School of Rutgers University. "The prints are so well preserved."

"The researchers identified the footprints as probably belonging to a member of Homo ergaster, an early form of Homo erectus. Such prints include modern foot features such as a rounded heel, a human-like arch and a big toe that sits parallel to other toes.

"By contrast, apes have more curved fingers and toes made for grasping tree branches. The earliest human ancestors, such as Australopithecus afarensis, still possessed many ape-like features more than 2 million years ago — the well-known "Lucy" specimen represents one such example.

"By contrast, apes have more curved fingers and toes made for grasping tree branches. The earliest human ancestors, such as Australopithecus afarensis, still possessed many ape-like features more than 2 million years ago — the well-known "Lucy" specimen represents one such example."Modern feet mark just one of several dramatic shifts in early humans, specifically regarding the appearance of Homo erectus around 2 million years ago. Homo erectus is the first hominid to have the same body proportions as modern Homo sapiens.

"We're seeing a very different hominid at this stage," Harris said, pointing to both an increase in size and change in stride during the relatively short time between Australopithecus (the first in this genus lived about 4 million years ago and the last died out between 3 million and 2 million years ago) and Homo erectus. The latter hominids would have been able to travel more quickly and efficiently over larger areas.

"This matches a pattern of more widely-distributed sites containing artifacts such as tools from 1.5 million to 1 million years ago, which may also point to wider-ranging early humans.

"Climate changing and shifting physical landscapes would have also forced the likes of Homo erectus to wander farther in search of food, Harris said. But increased walking and running abilities may have allowed them to start seriously hunting big game

"You might even think in terms of dietary quality here, because maybe they're incorporating more meat into their diet," Harris said. "They would have competed with quite a large carnivore guild; lions, leopards, and all the cats that eat meat."

"The Homo erectus footprints now lead further into the past of human evolution, as researchers may shift their focus to earlier examples of physical changes in human ancestor species.

"It's going to bring up controversy again about the Laetoli prints," Harris noted, referring to footprints preserved in volcanic ash roughly 3.6 million years ago in Tanzania. Anthropologists continue to debate whether these older footprints from an earlier "Lucy" type hominid show that Australopithecus walked about easily or awkwardly on two legs.

"Other findings may yet be revealed with the latest footprints at the Ileret site. The prehistoric landscape near various water sources was likely a muddy surface that preserved a whole range of animal tracks, Harris hinted — perhaps fodder for additional studies in the future."

"It really is a snapshot of time," Braun says. The preserved area also shows a wealth of animal prints, which gives more precise information about what creatures shared the space and time. Exhumed fossils can yield info on general environments; footprints can provide a glimpse into life over days rather than millennia. "With the footprints," Braun says, "we can almost certainly say these things lived in the same time as each other, which is unique."

"It is much rarer to find footprints than bones, because conditions must be perfect for tracks to be preserved, according to Braun. In this case, the tracks were made during a rainy season near an ancient river just before that river changed course and swept a protective layer of sand over them.

"The last major set of footprints, discovered in 1978 in Laetoli, Tanzania, were dated to about 3.6 million years ago. But those revealed a more ancient foot and gait, and it is still debatable whether those who made them had a stride more akin to humans or to chimpanzees, says Raichlen, who has studied the Laetoli prints.

"The Ileret tracks were digitally scanned using a laser technique developed by lead study author, Matthew Bennett, a geoarchaeologist at Bournemouth University in Poole, England. Raichlen says the find gives people a rare view of those that have trod before. "It's important to think about what you're really getting: a glimpse of behavior in the fossil record that you wouldn't really get in any other way," he says. The research reveals "a moment in time when individuals are walking around the landscape. It sort of fleshes out and brings them back to life, in a way."

No comments:

Post a Comment